Seminar: Science and Masculinities in History. A Global Perspective

Of the 24 prizes awarded by ETH Zurich, not one is named after a female scientist. This is despite the fact that there are many role models for young women scientists in the history of ETH. If we want women to feel as entitled as men to pursue a scientific career, the awarding policy at ETH ought to change.

Image 1: ETH's most famous alumni used as advertising tool for young talents.

In late 2018, there was a communication campaign from ETH to attract sponsors to fund the Excellence Scholarship for master students. The posters were picturing Albert Einstein doing student jobs (waiter, food delivery), stating: “Brilliant minds shouldn’t be distracted from their studies by part-time jobs”. While it is a strong message for potential sponsors because it is rewarding for them to think that they might be helping the next Einstein, there is a problem when it comes to the potential applicants for this scholarship.

Indeed, these posters give only one possible representation of what an excellent student looks like: a European male who is a genius. While the “European male” part makes it hard for minorities such as women and people of colour to feel included, the “genius” part makes it even harder. Students from minorities tend to have more self-censorship, so they will be less likely to think they can successfully apply for a scholarship because the model they see seems out of their reach.

During the same period, there was a campaign for the so-called Alfred Escher prize. It was at this time that I read some of the Equal! monitoring reports on gender equality at ETH. The 2017/2018 report was focusing on female role models at ETH. It analysed the proportion of female lecturers, of female mentors for projects and thesis, the commitment of women from several departments in feminine associations aiming at networking and promoting science towards girls.

Image 2: 'Even hipsters can become pioneers': Alfred Escher (1819-1882) was a Zürich politician, celebrated pioneer of modern Switzerland and initiator of ETH Zürich. On the occasion of his 200th birthday, ETH named a prize for young researchers after him.

But it does not speak about women’s representation in communication campaigns, even though these pictures and messages are visible everywhere in ETH buildings, in the ETH shuttle bus, on the ETH website, and even on the streets. It was for that reason that I became interested in the names of the prizes awarded by ETH, because I believe they can tell us a lot about what the institution values – and last but not least, what has to change in terms of gender equality.

SCIENCE AND THE EXCLUSION OF WOMEN

My analysis of the names of the honours and prizes awarded by ETH gave the following results: of the 24 prizes I could identify on the ETH website, 11 have neutral names (e.g. Crédit Suisse Award for best teaching, ETH Gold medal) and 13 carry the name of a person. Among these 13 names, there are 6 former ETH professors (2 of which have two prizes carrying their name: Richard R. Ernst and Aurel Stodola), 3 sponsors, 1 entrepreneur and 1 company name, Hilti, which is also the name of its founders (click here to download the complete list).

It is striking to see that for all prizes carrying someone’s name, this someone is a man (except for the Lopez-Loreta prize, which explicitly carries the surnames of both M. and Mrs. Lopez-Loreta). And yet, this might not come as a big surprise. Women have been deprived of scientific recognition since the very beginning of modern science. Jan Golinski explains in his work how back in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries men of science created a world from which women were excluded. Women were indeed regarded as unable to produce logical reasoning.

The situation is more balanced today, but subtle mechanisms subsist and continue to create a “glass ceiling”. For example, there are still biases in peer evaluation, with men being less likely to cite publications from women, and women applying for an academic position are being seen as less competent than equivalent male applicants.

FINDING FEMALE FIGURES

We can note that on the webpage for honours and prizes, there are two sections dedicated to women: “female prize winners” and “Female honorary councillors and honorary doctorate recipients”. Although this is a sign that ETH cares about gender inequality, it does not appear as a good solution to the lack of female role models in academia. Indeed, putting a short list of female awardees after a long list of prizes carrying the names of male scientists and awarded to an overwhelming majority of men does not kindle the feeling that women and men are equally capable of scientific discoveries. Only the Latsis prize has been awarded to an equal number of women and men since 2008.

In my opinion, one way to increase the recognition for female scientists would be to rename or create awards with women’s names. Finding such female figures is not difficult. Taking a look into ETH history, we can retain the names of Flora Steiger-Crawford and Flora Ruchat-Roncati, respectively the first woman to graduate in architecture and the first woman to acquire a full professorship at ETH. They were renowned and innovative architects at their time. Or Elizabeth Stephansen who was a mathematician and the first Norwegian woman to earn a doctoral degree, which she obtained at ETH.

There is also Mileva Maric, Albert Einstein’s first wife. She was an exceptional student at the time and at the least she discussed the content and proofread Einstein’s articles that he published while they were together. Lastly, we could look at honorary doctors of ETH: Donatella H. Meadows, a pioneering American environmental scientist and lead author of the epochal 1972 report on ‘The Limits of Growth’ commissioned by the Club of Rome, was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from ETH. Mildred Dresselhaus was known as the ‘queen of carbon science’ for her work on graphite and carbon nanotubes.

With that in mind, a big mistake would be to create only one prize carrying a woman’s name, and to award it to women only. This would only lead to less of the other prizes being awarded to women, and reinforce the idea that they need a dedicated prize because they are seemingly not as competent as men. The only way to treat men and women as equals is to have several prizes named after women of science, and to award prizes to men and women independently to the prize’s name.

Image 3: Mileva Maric, Albert Einstein’s first wife, was one of the first women to earn a degree in mathematics and physics.

SCIENCE IS COLLABORATIVE

Another possible approach would be to focus on research groups and discoveries rather than on exceptional individuals. Reducing the history of science to a few “geniuses” with ground-breaking ideas makes us forget that scientific research is most of the time a result of collaboration. For example, Einstein was not the only one to work on the theory of relativity: Poincaré was the first to use the well-known formula E = mc2 in an article based on a theory by Lorentz, and Einstein himself collaborated with his wife Mileva Maric and his friends Marcel Grossmann and Michele Besso to develop his theory.

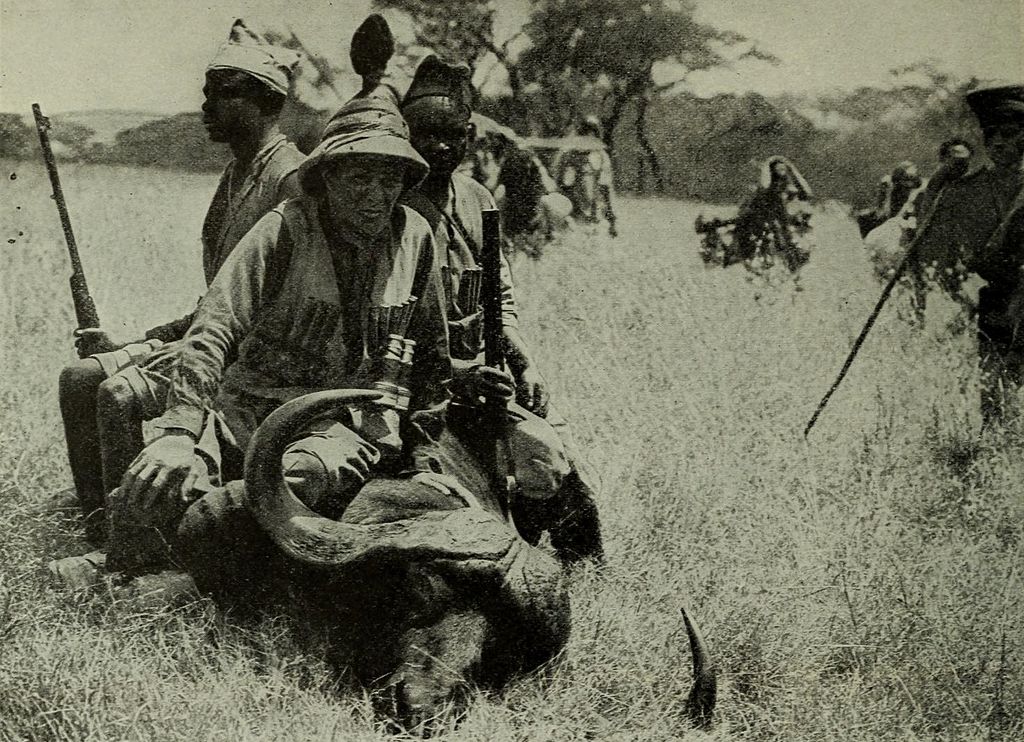

In a completely different field, Carl Akeley gave his name to the Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History. He was indeed a pioneering taxidermist, but he was not working alone: he had assistants and technicians, his safaris were organised by his wives and African natives were helping to find and hunt the animals destined to be stuffed. Both are examples for collective work, but in both cases a single “genius” received all of the credit and recognition.

Image 4: "Pioneer" Carl Akeley and his "gun boys" who helped him hunt animals for his taxidermic collections.

Furthermore, when one of the researchers taking part in a collaborative project is a woman, it is more likely for her to get none of the credit while her male counterparts do. This effect was studied by historian of science Margaret W. Rossiter, who called it the Matilda effect, named after suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage. Scientists such as Rosalind Franklin and Lise Meitner were victims of this effect when they did not get awarded a Nobel Prize but their male colleagues did.

Awarding prizes to research groups rather than to individuals could help avoiding this effect. However, this option requires that we generally rethink the history of academic research and the way it works today. We are used to associating a historical period or a great discovery with a few names, and perhaps retaining names of famous personalities makes us feel that the individual matters more than the collective. If we want that all contributors of a research project get the credit they deserve, this needs to change.

It is a general phenomenon, which is also present at ETH Zürich, that most scientific awards carry the name of a famous male scientist. This might be not that surprising as women were only recently allowed to study at universities, to teach and to publish articles, as compared to men who have been doing this for several centuries. Nevertheless, prize names perpetuate gender unbalance in scientific recognition because of their inertia.

To increase the number of female role models in science, it is important to address this situation and to create prizes named after great women forgotten by history, or belonging to very recent history. Moreover, it is important to put into question the necessity to distinguish and honour a few individuals even though scientific research is a collective process. This might require a lot of effort in reshaping the way we think academia in general, but this effort has to be taken if we want women to feel as entitled as men to pursue a scientific career.

Abbildungsverzeichnis

Image 1: Ruf Lanz / ETH Zurich

Image 2: ETH Zurich

Image 3: Unknown Photographer: Albert Einstein and his wife Mileva Maric, Public Domain. ETH Library: http://doi.org/10.3932/ethz-a-000045751

Image 4: Unknown Photographer: Mr. Akeley and his Gun Boys, in: Akeley, Carl E.: “Hunting the African Buffalo”, in: The World’s Work XLI (1921), pp. 497—504, here p. 500. Archive.org: https://archive.org/stream/worldswork41gard#page/500/mode/2upf

Literaturverzeichnis

Golinski, Jan. “The Care of the Self and the Masculine Birth of Science.” History of Science 40, no. 2 (2002): 125–45.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” Social Text, no. 11 (1984): 20–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/466593.

Schubert, Renate & Storjohann, Romila. “Gender Monitoring 2017/2018. Report on the Gender Balance between Women and Men in Studies and Research at ETH Zurich”. Zurich 2018.

Seminar

This text was drafted in the seminar ‘Science and Masculinity in History: A global Perspective‘ in the autumn semester 2018.

Redaktionell betreut von

Bernhard C. Schär & Monique Ligtenberg

Abbildungsverzeichnis

Image 1: Ruf Lanz / ETH Zurich

Image 2: ETH Zurich

Image 3: Unknown Photographer: Albert Einstein and his wife Mileva Maric, Public Domain. ETH Library: http://doi.org/10.3932/ethz-a-000045751

Image 4: Unknown Photographer: Mr. Akeley and his Gun Boys, in: Akeley, Carl E.: “Hunting the African Buffalo”, in: The World’s Work XLI (1921), pp. 497—504, here p. 500. Archive.org: https://archive.org/stream/worldswork41gard#page/500/mode/2upf

Literaturverzeichnis

Golinski, Jan. “The Care of the Self and the Masculine Birth of Science.” History of Science 40, no. 2 (2002): 125–45.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” Social Text, no. 11 (1984): 20–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/466593.

Schubert, Renate & Storjohann, Romila. “Gender Monitoring 2017/2018. Report on the Gender Balance between Women and Men in Studies and Research at ETH Zurich”. Zurich 2018.